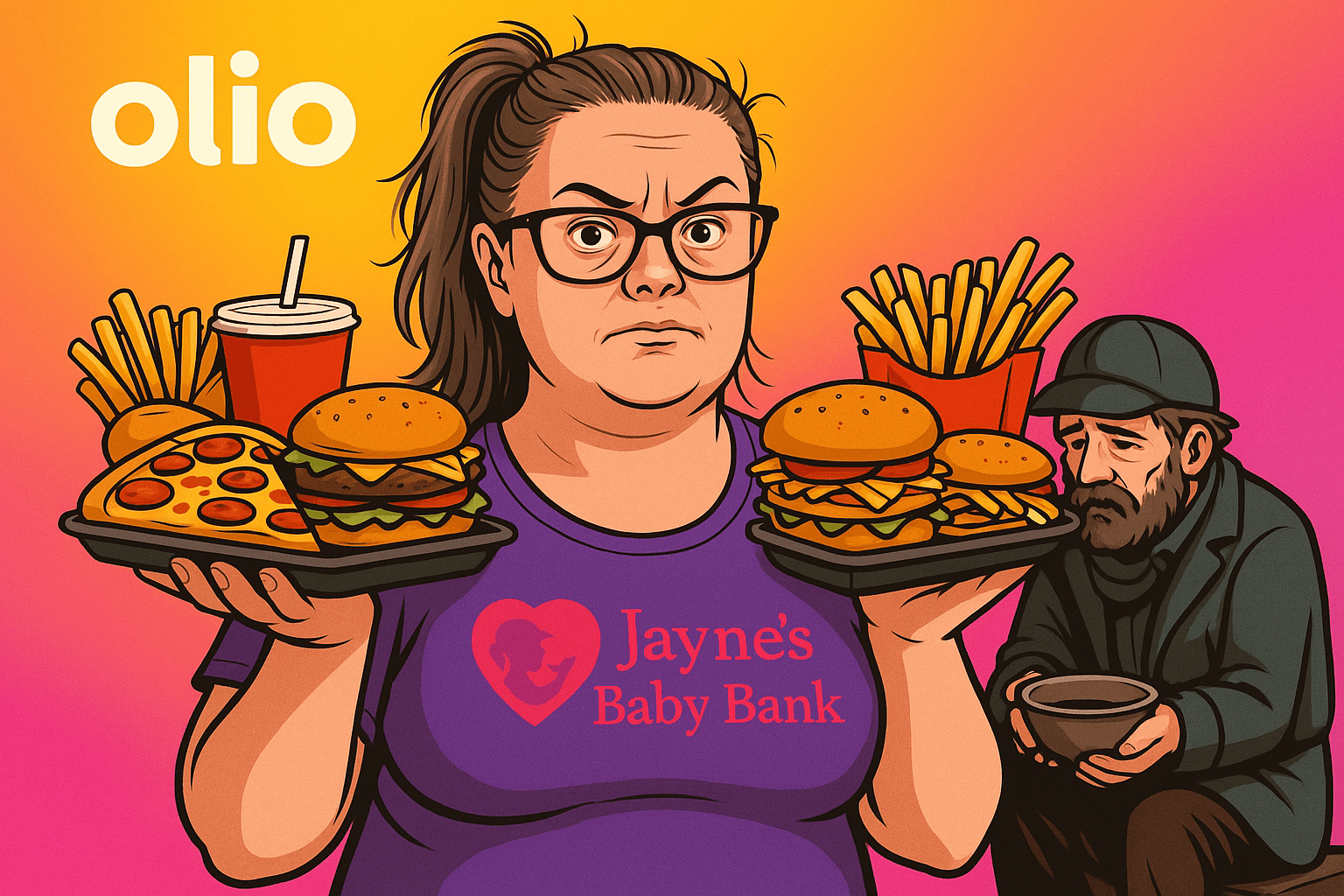

For years, “Jayne’s Baby Bank” has presented itself as a community lifeline. But insider leaks, FOI disclosures, and social media evidence paint a different picture. At the heart of the issue is food — supermarket surplus intended for redistribution to vulnerable families but diverted, restricted, or consumed by volunteers. This account lays out, step by step, what the insider evidence shows.

Trading Standards: Missed Opportunity

According to the whistleblower:

“Yes, the officer from Trading Standards was well aware of all the claims about JBB and desperately wanted for myself and the vulnerable person to go on record for the ‘higher ups’ to agree to a more in-depth investigation. When the signed witness statements were refused (I gave a lot of evidence from the vulnerable person, which should’ve been sufficient for investigation), TS became uninterested.”

The whistleblower then pursued their own complaints:

“So I made a complaint in my name only as a consumer about the use of charity on her stores and online. I also called Action Fraud with the same complaint. And I complained to Social Services about her claim to refer and support people get help for historic sexual abuse. Nothing was ever taken seriously, in my opinion.”

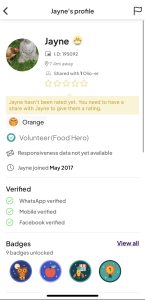

Banned from Olio and FareShare

The whistleblower confirms they intervened to cut off JBB’s food collection channels:

“I did get her banned as ‘Jayne’ on Olio and stopped from claiming Fareshare Go collections via Fareshare directly.”

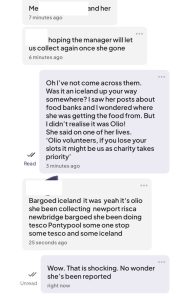

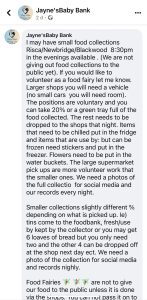

The Olio–Facebook Contradiction

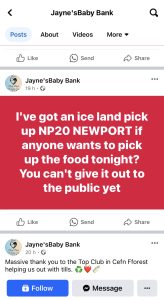

The leak highlights how food listed on Olio (2023–2024) was also shown on Facebook posts (2024–2025) with a different narrative. On Olio, collections appeared under Jayne’s own name. On Facebook, near-identical food was described in tiles such as “Iceland pick-up – You can’t give it out to the public yet.”

“Attaching the Olio evidence, all yours to compile against what is/was readily available on her Facebook profile. It shows her taking Olio food collections, diverting the food and claiming on Facebook to be from Fareshare, even when she was asked multiple times was it Olio food – she always deleted those comments very quickly.”

This practice risked misleading the public and may constitute misrepresentation under the Consumer Protection from Unfair Trading Regulations 2008 and potentially the Fraud Act 2006 (s.2 false representation).

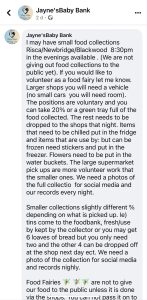

Recruiting Volunteers as “Food Fairies”

The whistleblower describes a deliberate strategy to enlist others into this practice:

“It also shows her trying to recruit volunteers to collect the Olio food on her behalf even though the collection slots were claimed by ‘Jayne’ and that food should’ve been listed on Olio – she would merely list one listing on Olio not to trigger a warning. Trying to get unsuspecting volunteers to collect food they legitimately thought was charity/fareshare while it was meant for Olio, makes them unwitting accomplices.”

Her own posts (September 2024) explicitly use the phrase “Food Fairy” to describe these volunteers.

Volunteer Skim / Built-In Diversion

Alongside the recruitment drive, public posts set rules that legitimised diversion of donations. One recruitment tile instructed:

“Volunteers can take 20% or a green tray full.”

This “skim” policy shows that food was systematically diverted to volunteers for personal use before families in need ever saw it.

Supermarket Awareness and Risks to Volunteers

The insider further noted:

“I am aware that a few stores were warned about what she was doing and those poor volunteers could well have been apprehended by store staff for trying to steal the food. And they would never have known they had been conned into doing so.”

This highlights the potential harm not only to families missing out on food, but also to individuals unknowingly put in jeopardy by following her instructions. Innocent volunteers could have been treated as shoplifters if challenged in-store.

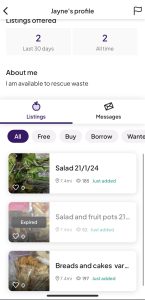

The “Breads and Cakes” Example

One clear contradiction is documented:

“Check the Olio listing attached for ‘Breads and cakes’ – you can see the same image used on her Facebook page claiming it’s a collection that they ‘can’t give out to the public yet.’ You’ll notice the Olio listing is in her name, not the volunteer she claims collected it.”

This example demonstrates the recycling of identical food images across platforms to disguise the true origin of the collections.

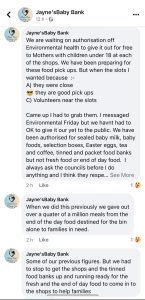

Community Backlash

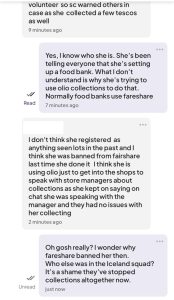

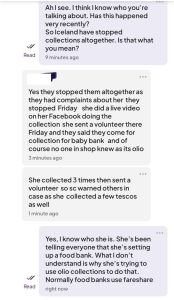

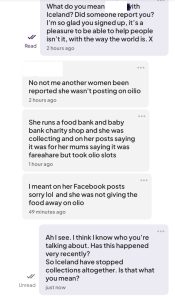

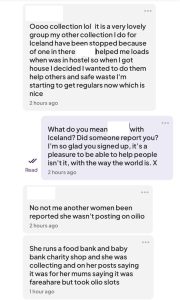

Screenshots from Olio chat groups (2023–2024) reveal that the wider volunteer community caught on and reported the behaviour. Several users discuss how collections were stopped due to complaints:

“She runs a food bank and baby bank charity shop and she was collecting and on her posts saying it was for her mums saying it was fareshare but took olio slots.”

“Yes they stopped them altogether as they had complaints about her… she did a live video on her Facebook doing the collection… of course no one in shop knew as it’s olio.”

Another chat explicitly states:

“Normally food banks use Fareshare. I think she was banned from Fareshare last time she done it… She is using Olio just to get into the shops.”

Further posts confirm supermarkets were aware and volunteers were anxious about reputational fallout:

“Bargoed Iceland it was yeah it’s olio… she been collecting Newport, Risca, Newbridge, Bargoed… Tesco, Pontypool, One Stop. No wonder she’s been reported.”

This community evidence corroborates the whistleblower’s account, showing how Jayne’s misuse of Olio slots directly triggered restrictions and bans across multiple supermarkets.

Why It Matters

The leaked insider account reveals how Olio collections were rebranded in Facebook posts, comments questioning this were deleted, and volunteers were misled into acting as “Food Fairies.” The recruitment scheme even permitted volunteers to keep a set percentage of donations. Families who should have received the food were sidelined, while those collecting risked being seen as shoplifters.

This activity undermines legitimate redistribution networks and jeopardises trust in community food supply chains.

Full leak archive

UPDATE: FareShare Confirms: No Affiliation

Following publication of this investigation, FareShare’s Charity Team formally confirmed in writing on 16 October 2025 that Jayne’s Baby Bank “is not, and has never been, a member of FareShare or received food via the FareShare Go programme.”

This directly contradicts repeated claims made on social media and in public statements by the operator of Jayne’s Baby Bank, who has referred to FareShare to imply official partnerships and legitimacy.

FareShare statement:

“Jayne’s Baby Bank is not, and has never been, a member of FareShare or received food via the FareShare Go programme.”

– FareShare Charity Team (Email, 16 October 2025)

The full correspondence is archived and available for reference as part of the public interest record.

Disclaimer: This article is based on leaked insider testimony, FOI records, and social media evidence. It does not constitute legal advice. For interpretation of food safety or consumer law, consult a qualified solicitor.

– Sherlock

Update – 16 October 2025: This article has been amended to include a verified statement from FareShare confirming that Jayne’s Baby Bank has never been a member or recipient of the FareShare Go programme. This directly contradicts public claims made by the operator. The amendment can be found at the bottom of the article under the section “FareShare Confirms: No Affiliation.”

– Sherlock

https://www.facebook.com/story.php?story_fbid=788712543916833&id=100083342834915

How do we counter that entire wall of text with a single image?

This one: https://jaynesbabybank.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/Carrie-Anne.png

Source: https://jaynesbabybank.co.uk/2025/08/28/carrie-anne-slips-up-live-real-name-real-fines-and-a-baby-bank-in-trouble/

S….

Automated Notice: New Transcript Alert

Speaker: Carrie-Anne Ridsdale (alias “Jayne Price”)

Issue Identified:

The speaker openly admits that her operation is not a registered charity. This directly conflicts with numerous public statements where “Jayne’s Baby Bank” has described itself as a charity or community organisation. It also undermines her claim of being supported or endorsed by local authorities.

Legal Framework:

Issue Identified:

The claim of “credibility” with enforcement agencies appears unsubstantiated. Freedom of Information disclosures from Torfaen Council and Trading Standards show no record of any formal endorsement or partnership. This could mislead the public into believing the enterprise is government-approved.

Issue Identified:

This statement indicates that the “baby bank” concept was initially used as a means of gaining access or legitimacy, not as a charitable or community-led initiative. It raises clear concerns about motive and transparency.

Issue Identified:

The speaker refers to receiving donations from individuals described as “hoarders” and working with “hoarding teams.” This creates both hygiene and safeguarding concerns if these items are resold to the public without professional cleaning, inspection, or consent.

Why this raises concern:

Legal Framework:

Issue Identified:

This comment trivialises the regulatory obligations of a legitimate charity and implies that operating outside of oversight is advantageous. It highlights a dismissive attitude towards compliance with the Charity Commission and Companies House frameworks.

Legal Framework:

Past UK Enforcement:

Recommended Oversight:

This transcript warrants review by Trading Standards (misrepresentation and retail regulation), Environmental Health (second-hand goods safety), and Adult Safeguarding under Torfaen Council if vulnerable individuals were involved. The Charity Commission may also investigate misuse of charitable descriptions.

– Sherlock

https://jaynesbabybank.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/SalvationArmy.pdf

Another problem coming your way, Carrie.

– S

Rebuttal: “Integrity Cannot Be Claimed — It Must Be Proven”

Published following Jayne’s Baby Bank’s public video response, 6 October 2025

Carrie-Anne Ridsdale, trading as Jayne’s Baby Bank, has released a fifteen-minute video attempting to discredit the whistleblower investigation. Her statements fail to refute any evidence and instead confirm core aspects of the report while introducing new falsehoods — including claims about a “fake Ukraine appeal.”

1. Confirmation of Food Diversion

This statement confirms that volunteers were instructed to retain food — a practice directly addressed in correspondence from Olio’s support team. Screenshots from Olio confirm that Carrie-Anne Ridsdale (using the account “Cerii”) was banned from the Food Waste Hero programme after multiple reports of misuse. The messages from Olio staff explicitly state that her collection privileges were revoked following complaints from participating stores and local volunteers.

Ridsdale’s attempt to justify her actions by citing a “10% rule” misrepresents Olio’s actual policy. While Food Waste Heroes may keep a small portion (up to 10%) of food for personal use, this rule applies only to authorised collectors operating within Olio’s active scheme. Once removed or banned, an individual is no longer permitted to collect or redistribute any food under Olio’s name.

Her additional claim of a “20% allowance” for FareShare is equally inaccurate. FareShare’s 20% reference concerns produce quality control — ensuring that no more than 20% of fruit or vegetables arriving at their depots show rot or mould. It is a safety measure, not an entitlement for any collector to keep food.

The combination of her confirmed Olio ban and her misrepresentation of FareShare’s internal inspection threshold further validates the whistleblower’s account of food diversion under false pretences.

2. Admission of Deceptive Branding

These remarks collectively amount to an unambiguous admission of deliberate misrepresentation. By describing Jayne’s Baby Bank as a “decoy,” Ridsdale confirms that the name functions as a shield brand — a distraction deployed to absorb scrutiny while other undisclosed activities continue elsewhere. Her further comment that the name was “sacrificed” reveals premeditation: the organisation was set up to be expendable once public attention intensified.

The notion of “doing something else” while the public focuses on the Baby Bank directly supports the documented pattern of parallel or successor operations such as Jarmani’s Charity Boutique, Second-Hand Land, and Community Shop One. Each has appeared after exposure or regulatory contact, featuring near-identical social media material, shop interiors, and staff, but under new branding. This pattern now stands confirmed in her own words.

Her additional quote — that she could rename the organisation to “Sue Anne Fields Memorabilia and Prostitution Museum” and still have people “turn up and buy” — goes further. It demonstrates open disregard for truthful representation and for the public’s right to know whom they are supporting. The statement implies that brand identity, honesty, and charitable status are irrelevant so long as sales continue. This directly contradicts her repeated public insistence on “integrity” and undermines claims of transparency or charitable motivation.

Taken together, these statements establish intent: Jayne’s Baby Bank is not an isolated project but a rotating trading identity used to preserve income and evade accountability. The language of “decoy,” “sacrifice,” and name-swapping confirms a pattern of concealment consistent with the rebrand trail already evidenced by public records, online archives, and whistleblower testimony.

3. Dismissal of Accountability

Such remarks reinforce her belief that brand identity and regulatory legitimacy are irrelevant. The admission that she can freely rename operations without consequence underlines a calculated evasion of accountability.

4. Justification of the “Volunteer Skim”

This policy formalised diversion of donated or surplus food before recipients saw it, matching whistleblower testimony.

5. Deflection and Personal Attacks

Ridsdale avoids the evidence and targets individuals. Examples from the video include:

Each of these statements reflects an escalating hostility and confirms a pattern of public intimidation, false superiority, and deliberate deception rather than factual rebuttal.

6. False Claims About “Donations”

A compulsory £1 to obtain goods is a sale, not a donation. Donations are voluntary. Labelling mandatory payments as “donations” misleads consumers regarding cost and charitable status.

7. The False “Ukraine Appeal” Narrative

Ridsdale repeats a claim that former charity founder Nicola Williams conducted a “fake Ukraine appeal.” Evidence now published refutes this.

Nicola Williams, founder of registered charity Cwtch-Up (1194295), has provided documentation showing delivery of aid to refugees in Przemyśl, Poland, near the Medyka–Shehyni border. Video evidence confirms she crossed into Ukraine to deliver supplies to a midwife operating a Polish Red Cross ambulance evacuating patients.

This directly contradicts claims that the appeal “never took place.” Further supporting material includes:

Video Evidence

Recorded at the refugee centre in Przemyśl, approximately 10 km from Ukraine, with subsequent aid handover across the border:

https://jaynesbabybank.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Cwtch_Ukraine.mp4

Historical Claims by Jayne’s Baby Bank

The newly released video evidence contradicts the above posts and confirms legitimate humanitarian delivery.

8. The Integrity Claim Revisited

Integrity is demonstrated through transparency and lawful practice. Admissions of decoy operations, misuse of donation language, and false public allegations are incompatible with integrity. Rather than evidence of honesty, her continued operation despite multiple complaints and bans points to loophole exploitation, not legitimacy.

Conclusion

These on-record statements and contradictions warrant review by relevant authorities and redistribution partners.

— Sherlock

⚖️ Legal Note

This report records statements, screenshots, emails, images, and direct quotes supplied to the investigation. It is not legal advice. Allegations remain unproven unless established by investigation or court process.

Automated notice: New Transcript Alert

Issue Identified:

The speaker again claims a formal entitlement to keep “10%” of redistributed supermarket surplus and asserts that her group continues to collect from Fareshare Go and Olio. Both statements contradict verified correspondence and screenshots showing previous removals and bans. Neither Fareshare nor Olio grant independent operators authority to divert or retain donated stock for personal or volunteer use outside prescribed conditions.

The additional claim about “getting another charity shut down” is factually unsupported and directed at Nicola Williams, the founder of Cwtch-Up (registered charity 1194295). Records confirm that Cwtch-Up voluntarily closed in 2023 following harassment and investigation pressure, not through any action by Jayne’s Baby Bank. Nicola’s whistle-blower material was key in exposing the food diversion issues that underpin these transcripts.

Policy Clarification and Contradiction

Olio’s volunteer policy allows a 10% personal allowance of surplus food and only after the remainder has been listed and shared through its platform. No such provision exists under Fareshare’s framework, which requires that all donated stock be distributed solely for charitable purposes.

Whistle-blower evidence linked to Jayne’s Baby Bank shows an internal rule that volunteers may “take 20% or a green crate full.” This exceeds Olio’s allowance and directly breaches Fareshare’s standards. The “green crate full” phrase illustrates a structured diversion policy rather than incidental retention.

Personal Attacks Against the Author (Sherlock)

The transcript contains repeated verbal attacks targeting the article’s author, accusing them of being “on drugs” and “on too much speed.” Such remarks are an attempt to delegitimise the investigation and distract from the underlying facts.

The pattern mirrors previous responses from Jayne’s Baby Bank whenever evidence is released. Instead of addressing documented bans and contradictory posts, the speaker diverts attention through insult and ridicule while continuing to restate the same disproven claims about authorised food collection, entitlement to stock, and success in “shutting down” rival organisations.

Context and Timing

This livestream followed shortly after publication of evidence detailing Fareshare and Olio restrictions. The broadcast repeats prior misrepresentations and adds a new falsehood regarding the closure of Nicola Williams’s registered charity, Cwtch-Up. The timing and tone show an effort to reassert legitimacy, reinforce a loyal audience, and deflect from verified misconduct rather than engage with evidence.

– Sherlock

Automated notice: New Transcript Alert

Admission of operating without registration while soliciting food and donations, creating a misleading public impression of legitimacy and accountability.

Confirms a standing policy allowing volunteers to keep donated food before it reaches families, showing intentional diversion of goods.

Reveals personal consumption of donated supermarket food, undermining claims that all items are redistributed to those in need.

Demonstrates the internal justification used for diverting surplus food and donations outside authorised redistribution schemes.

Shows direct reference to supermarket partnerships and FareShare links despite earlier evidence of bans and restrictions.

Overstated operational claim used to project scale and credibility.

Confirms recruitment of “volunteers” compensated with donated goods, suggesting undeclared employment and misuse of donations.

Contradicts earlier statements confirming volunteer skims and personal retention of food.

This figure was not generated by Jayne’s operation. It matches verbatim data published by Cwtch-Up, misappropriating another group’s metrics to inflate legitimacy.

Displays hostile conduct towards other organisations, further undermining credibility and professionalism.

Closing analysis

The timing of this livestream, posted immediately after documented evidence and screenshots of bans from Olio and FareShare, indicates attempted narrative control. The quotes above reconstruct a false impression of scale, legitimacy, and support while contradicting verified restrictions and showing diversion of food to volunteers and for personal use. As previously documented:

This transcript operates as live proof of the same deception in motion.

– Sherlock

How can we logically conclude that Carrie Anne of Jayne’s Baby Bank has seen this status and is trying to work around it? Simple. She posted the following less than an hour ago:

You may think this is a routine status, but it is not. It is 100% damage control.

Apply logic. Our transcript search shows only three archived posts that mention OLIO, including this new one. The previous instance was on 10 June 2023. See the search results for “olio”. What are the chances an OLIO post appears within 24 hours of this going live? Coincidence?

Use logic.

– Sherlock

Looks like the post today is a share of a memory without making it clear it’s such, it’s the exact same wording as one of the ones you’ve archived.

I reported her to CCBC trading standards and environmental health over these collections and I spoke to a member of staff in a local Icelands who was going to stop her collecting as they though it was being given to people in need and not being kept for family and volunteers.

We fully expect her to purchase short-dated items at a reduced price from a supermarket, purely to post about them on Facebook as a form of narrative control. The link we shared contained three results; the one identical to her Facebook post originates from our backup system archive, confirming it is not a duplicate.

LINK: https://jaynesbabybank.co.uk/search/?search=olio&limit=50&sort_order=relevance&search_type=posts&open_transcript=785646820890072_1759581399_fb.json

The top left displays today’s date.

– Sherlock

Using the Ian and Hayley incident as a shield will not protect you, Carrie. Both appear so focused on each other’s downfall that they overlook how damaging their conduct appears to the public. You have engaged in similar behaviour.

To be charitable is to offer help or resources without expectation of return, particularly to those in need. To be kind is to act with fairness, patience, and consideration towards others. To be loving is to value others and act for their wellbeing, even when there is no personal gain.

Your public statements about “manifestation” do not align with reality. You have experienced a steady decline in followers since your “72,000 followers” claim and may fall below 70,000 before Christmas. If Facebook removes inauthentic or automated accounts, your reach will diminish further.

Your online behaviour contradicts your stated aims. In another context, your persistence and drive could have been used productively, yet you chose to exploit vulnerable individuals. You have alienated supporters and criticised volunteers while attempting to maintain appearances. Personal health claims do not erase the harm caused to others.

Perhaps my law of attraction serves to counter your manifestation. Further verified materials will be published in due course here:

https://jaynesbabybank.co.uk/jaynes-baby-bank-images

– Sherlock

Very predictable. But as Molly says, it’s an old post. She has yet to post up to date photographs of her foodbank, top up shop and nappy bank, but then again do they exist?

The status update appears recent, as shown by the “Meta AI” label in the bottom right corner — a feature introduced in the UK on 9 October 2024. Therefore, if it is a shared “memory”, she is being deceptive. The link we shared contained three results; the one identical to her Facebook post originates from our backup system archive, confirming it is not a duplicate.

LINK: https://jaynesbabybank.co.uk/search/?search=olio&limit=50&sort_order=relevance&search_type=posts&open_transcript=785646820890072_1759581399_fb.json

The top left displays today’s date.

– Sherlock

https://www.facebook.com/story.php?story_fbid=785049770949777&id=100083342834915

Pennywise is a sinister clown who targets children, using tricks, illusions, and fear to lure its victims and feed on their terror.

It was defeated when the children, later as adults, stood together. By overcoming their fear and denying its power, they drained its strength until it could no longer hold its form and was destroyed.

She poses as Pennywise for effect, but the real fright is a phantom charity funding a cartomancer con — terror traded for trickery.

https://www.facebook.com/story.php?story_fbid=784934270961327&id=100083342834915

Sherlock

The Illusion of “Free” Goods – A Closer Look at Jayne’s Baby Bank

A TikTok video shared by Jayne’s Baby Bank shows boxes of donated baby items labelled “Free to Customers + Donators.” Source:

https://www.tiktok.com/@jaynesbabybank1_tm/video/7556947947657710870

This wording is legally problematic. UK law — including the Consumer Protection from Unfair Trading Regulations 2008 and Advertising Standards Authority guidance — mandates that “free” means exactly that: no payment, no hidden conditions, and no strings attached.

By conditioning “free” items on being a customer or donator, the claim misleads. It suggests universal availability while hiding eligibility constraints. This practice risks breaching consumer protection law and misleading the public.

Charitable intent does not remove the obligation for transparency. Donors and families deserve clarity, not marketing dressed as kindness.

– Sherlock