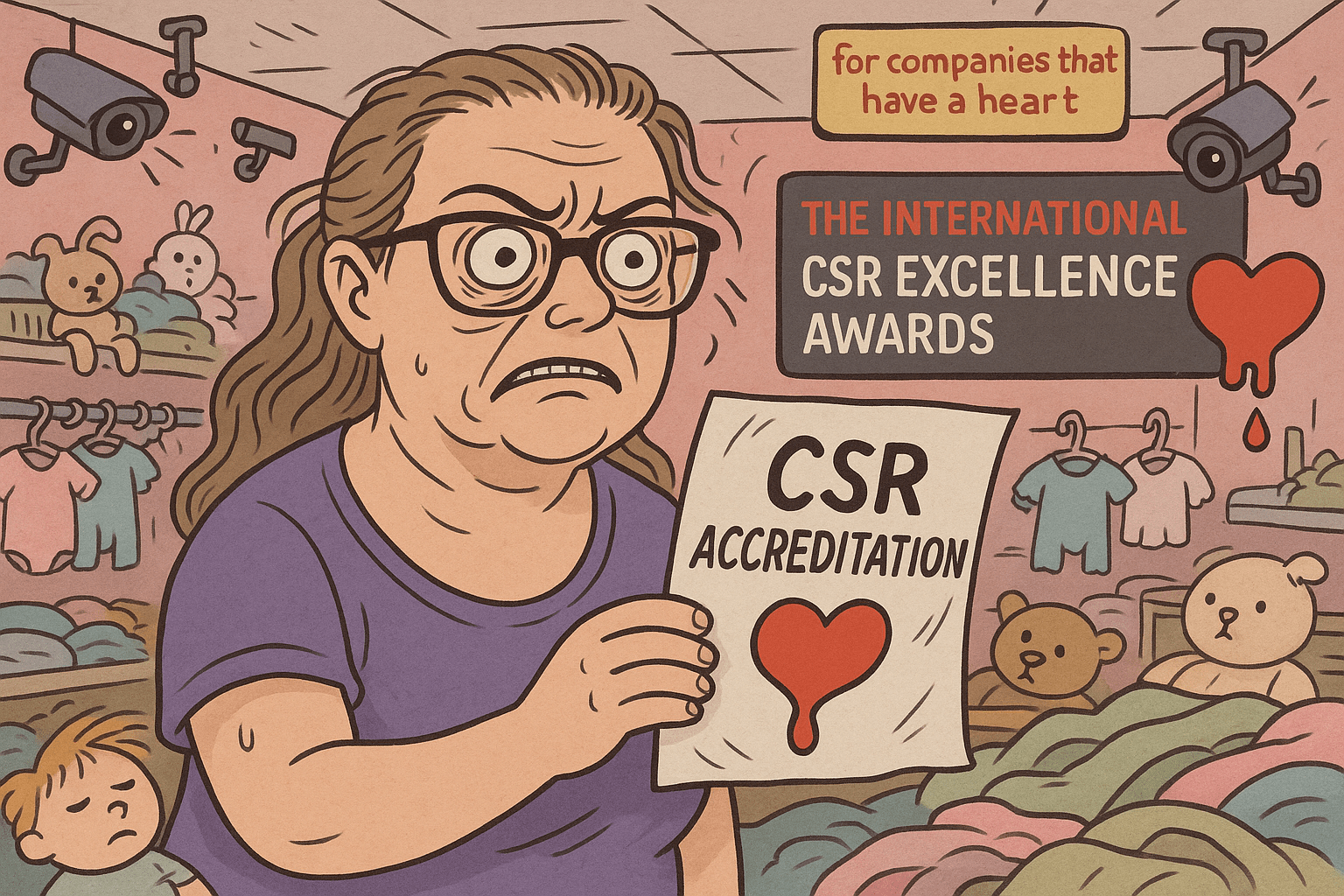

Across multiple Facebook posts — including 28 December 2024, 4 February 2025, and 23 September 2025 — Carrie-Anne Ridsdale (alias “Jayne Price”) has repeated the claim that Jayne’s Baby Bank has “won a sustainability award by the CRS Accreditation.” The wording implies independent accreditation of the organisation as a whole. In reality, the award process tells a different story.

What CRS/CSR Actually Is

The reference appears to be to the CSR Awards operated by The Green Organisation (also known as The CSR Society). These are not accreditations, nor endorsements of companies in their entirety. They are commercial awards based on self-submitted projects. Winners are recognised for individual initiatives, not for overall organisational conduct, and there is no link to the Charity Commission or any regulatory body. Jayne’s Baby Bank is listed on the 2024 International CSR Awards winners list. However, the project was recognised in isolation, not as proof that the operation itself is sustainable or accredited.

Note: In every public post, Ridsdale uses the phrase “CRS Accreditation.” No such body exists. The correct reference is to the CSR Awards. This recurring error itself undermines the credibility of the claim.

Conflicting Explanations from the Organiser

When The Green Organisation was asked for clarification, the responses shifted within hours. On 16 September 2025 at 14:31, CEO Roger Wolens wrote:

“Our CSR Awards are presented in connection with specific projects of a company or individual and this particular campaign relates to recycling and re-using unwanted baby clothes.”

Yet later the same day, at 17:38, the justification changed:

“Any awards we make are in recognition of specific projects; they do not endorse any company as a whole. The project in question is genuine and not without merit, so we will not withdraw the award on this occasion… As the award was made in 2024, it is not readily visible on our website, so I would suggest the chances of further exposure are very limited.”

The contradiction is clear. At one moment the award was linked to “recycling baby clothes,” hours later it was defended as a project under “food & drink” and “healthcare.” Such shifting explanations demonstrate the absence of consistent criteria and reinforce that these awards are not subject to independent verification.

Why the Claim is Misleading

By advertising on social media that Jayne’s Baby Bank had “won a sustainability award by the CRS Accreditation,” Ridsdale presented the award as an organisational accreditation. Examples include:

- 28 December 2024 – “We have also won two sustainability awards from the CRS Accreditation in London.”

- 4 February 2025 – “We have won 2 sustainability awards by the CRS Accreditation.”

- 23 September 2025 – “We have won a sustainability award by the CRS Accreditation.”

In reality, it was a project-level recognition in 2024 with no wider legal or regulatory significance. The awards cannot be described as accreditation, nor do they provide any endorsement of ongoing operations. This inflation of a limited project award into a blanket organisational credential fits a wider pattern of exaggerated claims used to establish false legitimacy in the eyes of donors, volunteers, and the public. The Green Organisation itself was explicit: their awards do not endorse companies as a whole. Any suggestion otherwise is inaccurate.

Disclaimer: This report is based on correspondence with The Green Organisation, public listings on csrawards.co.uk, and archived Facebook statements by Carrie-Anne Ridsdale. It is presented in the public interest and does not constitute legal advice.

– Sherlock

https://jaynesbabybank.co.uk/2025/06/20/fact-checking-carrie-anne-ridsdales-alleged-ba-hons-nursing-degree/

We’ve posted a new comment here regarding today’s claims and previous claims.

– Sherlock

Automated Notice: New Transcript Alert

Issue Identified:

Civil employment dispute reframed as a safeguarding cover-up. Suggests an apprentice was silenced for raising concerns and lost his role. This appears to inflate an ACAS/tribunal matter into a criminal safeguarding allegation.

Issue Identified:

Unverified allegation of sexual assault escalated into hypothetical rape and murder scenarios. Severe reputational harm risk. High exposure under the Defamation Act 2013.

Issue Identified:

Misrepresents UK defamation law. Truth is a defence only if supported by evidence. Broadcast claims of apprentices “not lying” do not meet the evidential standard in civil law.

Issue Identified:

Recounting of a hostile public altercation. Names family members, questions paternity, and portrays them as abusive. Risks falling under Protection from Harassment Act 1997 if repeated.

Issue Identified:

Threatening undertone. Implies retaliation against critics by exposing damaging information. This coercive style mirrors prior confrontations (e.g. Pontypool incident). May amount to intimidation or harassment.

Issue Identified:

Publicly states individuals are “going to be prosecuted” for assault/harassment. Prejudicial unless confirmed by CPS. Risk of contempt of court and reputational harm.

Issue Identified:

Admits to multiple altercations at home and shops, then insults individuals publicly. Hostile targeting of families and repeated online exposure risks breaching Malicious Communications Act 1988.

Issue Identified:

Historic allegation of theft tied to the same individuals. Adds to a pattern of criminal claims without evidence. High risk under Defamation Act 2013.

Legal Framework:

Health / Safety Concerns:

Past UK Enforcement:

Enforcement Remedy:

Potential action from Police (harassment, malicious communications), Crown Prosecution Service (if contempt arises), Charity Commission (if misrepresentation threatens charitable status), and Trading Standards (misleading trading practices presented as charitable activity).

– Sherlock

Automated notice: New Transcript & Deleted Post Alert

Speaker: Jayne’s Baby Bank (Carrie-Anne Ridsdale, alias “Jayne Price”)

Context: This livestream allegation reflects earlier public Facebook posts (since deleted) from an account named Jordan West and others discussing Snug Coffee Shop. Those posts included claims of:

The livestream essentially recycles these now-removed posts, reshaping them into a spoken narrative. No documentary evidence has been provided to support the allegations.

Issue Identified: UK law does not support this view. Under the Defamation Act 2013, serious allegations against named people or organisations must be evidenced. Without substantiation, repetition of deleted posts in a livestream still carries risk of defamation and harassment.

Legal Framework:

Contradictions & Risks:

Health / Safety Concerns:

Past UK Enforcement:

Enforcement Remedy:

Regulators (Trading Standards, Charity Commission) and law enforcement can act where livestreams misuse “charity” status or cross into harassment. Civil remedies include injunctions or damages for defamation. Police may investigate malicious communications or public order concerns.

– Sherlock

Status Update (Quoted)

What Aldi Actually Says

Aldi runs routine Lacura product giveaways via its Cult Beauty Club. According to Aldi’s press centre, the intent is:

The Issue

Instead of following Aldi’s review-led guidelines, the bundle has been used to drive personal social media engagement (likes, shares, tags) and platform growth. That’s a shift from product feedback to self-promotion, and it undermines the original purpose of the giveaway.

Why This Matters

Bottom Line

The Lacura bundle appears to have been repurposed for personal promotion rather than compliant, feedback-driven reviewing as set out by Aldi.

— Sherlock

Source: Facebook story

Context: Referenced video

Follower Numbers

The account now sits at around 71,000 followers, but it has been losing about 33 per day since the post went up. Many of those followers were deliberately added by us as part of a controlled test. The aim was simple: observe whether they would later be promoted as genuine supporters. This clarifies how public follower counts are presented versus what’s actually behind them.

Behaviour on Video

From the publicly visible clips, we see a pattern that conflicts with the image of a caring, charitable figure. Examples include mocking and laughing at mothers in need, criticising partners, making claims about unsolicited images, and live-streaming other people’s profiles. It’s not difficult to see how this could alienate genuine supporters.

Operational Outgoings (Estimates)

Total running costs: Pontypool £1,220 + Caerphilly £580 + Risca £580 + Storage £1,000 = £3,380/month

(Figures are indicative based on available information and may require verification.)

Verification

Business rates can be checked via the official portal: Find a business rates valuation.

Point of Interest

If business rates relief is being claimed on a charitable basis while publicly stating “not a charity”, that warrants closer scrutiny.

— Sherlock

Ms Ridsdale is now callng her shops Recycle Right Shops. She is advertising on a Pontypool Facebook site. No mention of it being a baby bank or foodbank.

A tongue in cheek look at Carrie Anne Ridsdale’s new website – ‘Recycle Wrong Shops’ are located at:-

5 Crane Street Pontypool

14 Pentrebane Street Caerphilly and 68 Tredegar Street Risca

Located by following the detritus on the pavement outside.

All sorts of vintage and retro crap can be found thrown on the floor or in overcrowded cabinets. Selected Clothes and shoes reduced to £1 (because no one else wants them). Card and contactless only we do not accept cash (as we cannot be trusted) and we don’t trust our volunteers not to steal it.

We take all donations, (due to an uncurable hoarding disorder). We do not collect or deliver (we now make other people do it for us) . We do not take offers – prices are set (in a totally random and ad-hoc fashion, whilst doing live feeds, talking BS for hours on end and defaming all and sundry).

Re – sellers pay the full price not offer prices (I’m telepathetic and can immediately tell the difference between a reseller from any other customer) and we don’t tolerate rude customers (but I myself can be as rude as I like). Thank you in advance for not believing any of my lies or BS.

You’re going to make her manifest a live video response. 😃

– Sherlock

It’s been a busy week overseeing my ebay empire, I could do with a good laugh 🤣

Well said! A much more accurate description of this despicable, vile woman’s rip off shops.

5 Crane Street Mon- Sat 10-4

Pontypool open Sunday

14 Pentrebane Streer Mon- Sat 10-4

CAERPHILLY closed this Saturday

68 Tredegar Street Mon – Friday 10-4 approx

RISCA High Street

All sorts of vintage and retro items. Selected Clothes and shoes reduced to £1. Card and contactless only we do not accept cash.

We take all donations. We do not collect or deliver. We do not take offers – prices are set. Re – sellers pay the full price not offer prices and we don’t tolerate rude customers. Thanks in advance.

How would she know if we’re resellers? I bought some china from the Pontypool shop last year. Priced at £25 for the bundle. When I got the set out of the cabinet they were priced at £2 each (£12 in total – 50% off = £6). I refused to pay the £25 and told the lady in the shop you can’t price things individually and then bundle them together and double the price. She tried to phone the manager to no avail. I got them for the bargain price of £6. Sold them on ebay for £60 as 1840’s antique plates. JBB stick that up your proverbial ****!!

Also been in the shops since my apparent ban and bought some Delft plates, also sold at a £10 profit. How on earth is she going to stop resellers. We don’t go in the shops with a tattoo on our forehead. What she seems to forget is the baby bank gets their money and once sold becomes the property of the buyer. What we choose to do with it after that is none of her business.

Automated Notice: Transcript Commentary

Speaker: Carrie Anne Ridsdale of “Jayne’s Baby Bank”

Fundraising via Meta: The speaker references income from Meta/Facebook. This appears to confirm that social media monetisation is being treated as a funding stream for the operation. However, no transparency is provided on how these funds are recorded or applied.

Contradictory Claims: The speaker describes the operation as a “not-for-profit business” rather than a charity, while also confirming commercial trading. Public communications elsewhere have promoted the operation as a “baby bank” or “food bank”, which appears inconsistent with this admission of business trading activity.

Transparency & Accountability: The refusal to provide accounts to the public is noted. While HMRC and local authorities may hold oversight powers, members of the public donating under the impression of charitable purpose could reasonably expect accessible financial reporting.

Status Clarification: Here the speaker explicitly denies charitable status, instead describing the operation as a personal “fundraising shop”. This conflicts with repeated public-facing claims presenting the enterprise as a baby bank comparable to charitable food banks.

Regulatory Oversight: The claim that shops are “exempt” from environmental health and food hygiene appears inaccurate. According to Environmental Health guidance, exemptions are limited and do not apply where food is handled, stored, or distributed.

Second-hand Car Seats: The transcript confirms circulation of second-hand car seats. While the speaker acknowledges restrictions under standards law, this raises safeguarding concerns. Trading Standards has previously intervened in similar cases.

Sexual Assault Allegations: The speaker makes public allegations about a third-party organisation and repeats a claim of police investigation. If unverified, such allegations carry legal risk and appear designed to undermine competing groups rather than provide evidence-based accountability.

Attacks on Critics: Rather than engaging with evidence, the speaker accuses the author of being under the influence of drugs. This language appears to be an attempt to discredit scrutiny and deflect from substantive questions.

ASA and Charity Law: The speaker admits that false charity claims could breach regulations, but distances herself by saying she is not a charity. This is contradicted by evidence: one video circulated publicly included Baby Bank branding as a watermark, with audio stating it was a “Giant Charity Shop” (sourced from Becky’s Bazaar, 2 July 2023). This demonstrates her operation has been publicly presented as a charity shop, undermining her defence.

Issue Identified

The transcript highlights recurring contradictions: denial of charity status while presenting as a baby bank; refusal of financial transparency; inaccurate claims of exemption from regulation; resale of second-hand child car seats; serious sexual assault allegations about other groups defended under “free speech”; personal attacks portraying critics as drug users; and an acknowledgement that false charity claims breach ASA/charity law, despite public material describing the shop as a “charity shop”.

Legal / Regulatory Framework

Health / Safety Concerns

Enforcement

Trading Standards, ASA, Environmental Health, HMRC, and the Charity Commission each hold powers relevant to the issues raised. Remedies could include product seizures, fines, mandated compliance, withdrawal of misleading claims, and inquiries into misrepresentation. Civil defamation action may also be engaged where allegations are unverified.

– Sherlock

Automated Notice: Transcript Commentary

Speaker: Carrie Anne Ridsdale of “Jayne’s Baby Bank” (also referred to as “Jayne’s Baby Bank shop” in the transcript)

QUOTE:

Issue Identified: Donation drop-offs appear to be occurring outside the premises, where goods are vulnerable to theft and contamination. This raises questions about safe custody of donations and basic site controls.

QUOTE:

Business Model & Public Representation: According to the transcript, donations are described as belonging to a “baby bank”, while specific resale pricing (£5 per record; “three for a pound”) and commercial sourcing (“two record shops feeding me with records”) are also stated. This appears to suggest a retail fundraising model operating alongside (or instead of) charitable distribution. The mixed presentation may be confusing to the public and appears inconsistent with prior characterisations of a “baby bank”.

QUOTE:

Payments & Consumer Transparency: Card-only trading is stated. This reinforces that on-site activities include retail sales to the public, which should meet relevant consumer protection and receipt/record-keeping standards.

QUOTE:

Record-Keeping: The transcript indicates a self-maintained ledger (weights, sales, notes of free items). This raises questions about whether these systems meet the record-keeping expectations applicable to the stated activities (e.g., charitable fundraising records, retail sales audit trails, and any tax/financial reporting duties).

QUOTE:

Stock Restriction Policy: A two-week “restriction” is described to maximise resale value. While framed as fundraising, this appears to prioritise revenue generation over immediate aid distribution, which may be perceived as inconsistent with a community “baby bank” identity.

QUOTE:

Health / Safety Concerns:

Issue Identified

According to the transcript, the operation is presented as a “baby bank” serving the public, while also describing routine retail trading, commercial stock inflows, resale pricing, and stock restriction policies. This appears to suggest potential inconsistencies in how the enterprise is held out to donors and customers.

Legal Framework (indicative)

Past UK Enforcement

Enforcement Remedy

Depending on evidence and local jurisdiction, Trading Standards may investigate misleading practices; the Charity Commission may examine governance and public benefit claims where charitable representations are made; Environmental Health can assess storage/handling risks; and HMRC/Companies oversight concerns may arise around sales income and record-keeping. Remedies can include requiring corrective information, improvement notices, seizure/testing of goods, fines, and (where applicable) prosecution or regulatory action.

– Sherlock

Automated Notice: Transcript Commentary

Speaker: Carrie-Anne Ridsdale (alias “Jayne Price”)

Unsafe Clothing & Flammability: The speaker correctly cites the law on destruction of unsafe children’s nightwear, yet later suggests such items could be sent abroad. This appears inconsistent with the General Product Safety Regulations 2005 and Nightwear (Safety) Regulations 1985. Exporting flammable products shifts the risk to vulnerable families overseas rather than preventing harm as UK law requires.

Car Seats & Restraint Systems: Admission of stockpiling second-hand car seats, which are unsafe without traceable history. UK law under the Road Traffic Act 1988 and product safety regulations prohibits their resale or distribution. Publicly denying they are “for sale” while storing them raises risk of Trading Standards intervention.

Baby Bottles & Hygiene Risks: Bottles rejected by other baby banks are accepted here and proposed for export. Used infant feeding equipment risks bacterial contamination and chemical leaching. The Food Safety Act 1990 and UK food contact regulations prohibit unsafe bottles from circulation, even when donated.

Cosmetics & Second-hand Items: Redistribution of used cosmetics breaches the UK Cosmetic Products Enforcement Regulations 2013. Lip products in particular can transmit infection. Identifying them vaguely and leaving them in a “free box” demonstrates no compliance checks or product safety assurance.

Contradictory Claims: Public statements have both denied and claimed to stock haberdashery. Such contradictions undermine credibility and may constitute misleading commercial practice under the Consumer Protection from Unfair Trading Regulations 2008. Transparency is a core requirement under both consumer law and Charity Commission guidance.

Financial Transparency: Sponsorship and crowdfunding appeals are described, but blurred with references to personal and household spending. This raises questions under the Charities Act 2011 about clear separation of charitable funds from private use, and the Companies Act 2006 if operating as a business.

Volunteer Management: Vulnerable older people are being recruited ad hoc with no mention of training, insurance, or health and safety protocols. The Health & Safety at Work Act 1974 and Charity Commission safeguarding guidance both apply to volunteer environments.

Safeguarding Disclosure: A safeguarding allegation of extreme seriousness is broadcast publicly, despite requests for discretion. This risks breaching the Data Protection Act 2018 and prejudicing investigations. Charity safeguarding duties under the Children Act 2004 demand confidential and structured handling of such disclosures.

Age-restricted Sales: The sale of knives is discussed casually with shifting age limits (“21 or 25”). UK law sets 18 as the legal limit under the Offensive Weapons Act 2019. The informal approach described risks illegal sale and prosecution.

Staff & Customer Safety: Reliance on “no cash” as the primary safeguarding measure indicates the shops are perceived as unsafe. No evidence of safeguarding policies, staff training, or risk assessments is described, contrary to duties under the Health & Safety at Work Act 1974 and Safeguarding Vulnerable Groups Act 2006.

Exporting Unsafe Goods: Stock not compliant for UK use (car seats, bottles, clothing) is proposed for export to Uganda. This risks breaching international controls such as the Basel Convention and undermines UK product safety law. Exporting banned items to vulnerable communities abroad is both unsafe and ethically questionable.

Sustainability Claims: The operation is branded as “sustainable” while simultaneously describing practices such as exporting unsafe goods abroad. This appears contradictory and may amount to “greenwashing” under the Consumer Protection from Unfair Trading Regulations 2008. Misleading sustainability claims risk public trust.

– Sherlock

She had two car seats for sale in Caerphilly this week, she showed them on a video and said the cover to one of them was in Pontypool.

What has happened to the Donation Centre? The shops are overfilled and there is no space. How do customers find anything? How are the shops accessible to young mother’s with pushchairs or the disabled? There are so many references to businesses closing. She does not run a business. She buys no stock, pays no wages. Donations are sold for pennies. When will accounts be available for transparecy.

From the Donation Center transcripts (newest first), there are repeated admissions that the Center and the shops are at or beyond capacity. This appears to support the concern that “the shops are overfilled and there is no space”, with obvious knock-on effects for accessibility (pushchairs, wheelchairs) and safe circulation.

QUOTE:

QUOTE:

QUOTE:

QUOTE:

QUOTE:

Sherlock’s analysis: Taken together, these statements appear to confirm a persistent capacity problem at the Donation Center and in the shops. When premises are “quite full” to the point that customers are kept outside, this raises questions about accessibility and basic shop safety. According to public guidance under the Equality Act 2010 (reasonable adjustments and accessible layouts) and general duties under the Health and Safety at Work etc. Act 1974 (including safe means of access/egress and avoidance of trip hazards), over-stocked aisles and blocked circulation space can impede young mothers with pushchairs and disabled customers. This appears inconsistent with safe, accessible retail practice.

It also appears—from the same transcripts—that surplus stock keeps being routed back into the Donation Center (“that racking is going to be full”), which suggests a systemic stock control issue rather than a short, one-off spike. This directly speaks to the commenter’s point about “how do customers find anything?”—if display areas double as storage, basic wayfinding and product access are likely compromised.

On transparency and accountability: The question “When will accounts be available for transparency?” remains valid. According to public records criteria, if an operation is presented as charitable or community-benefit led, publishing clear financial information helps evidence that sales income is used to maintain safe, accessible premises (adequate staffing, storage, racking, and floor management). The transcripts do not, by themselves, provide those accounts; they instead highlight capacity pressure and operational strain.

In summary: The transcripts themselves acknowledge that the Donation Center and shops are frequently overfilled, which appears to undermine accessibility and safe circulation. This supports the commenter’s concerns and suggests the need for immediate space management measures and clear public reporting on how donations and sales are being managed to remedy these issues.

SOURCE: Donation Center transcript search (date-ordered)

– Sherlock

IMAGE: https://jaynesbabybank.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/HCT.png

SOURCE: https://www.facebook.com/photo?fbid=509728228481934

We believe you ought to give greater prominence to genuine food banks and charities in your shops. It would be beneficial all round. Perhaps place them front and centre so people can actually notice them?

– Sherlock

Automated Notice: Transcript Commentary

Speaker: Carrie-Anne Ridsdale (alias “Jayne Price”)

Business Operations: The speaker openly describes shifting premises and collecting shop furniture. This is retail preparation, not charitable food distribution.

Stock Collection & Distribution: Multiple carloads of donations are being managed as retail stock. Volunteers and even family members are enlisted to collect from other charity shops, which blurs lines between genuine donation work and commercial sourcing.

Regulatory Position: Despite claiming exemption from food safety rating, the speaker acknowledges Environmental Health oversight. The fixation on a “food rating” contrasts with the retail trading described, raising questions about what official category the operation truly falls under.

Accusations of Others: The speaker criticises other groups for “selling free food” and running “fake food banks,” yet simultaneously describes her own retail sales and donation stock handling. This contradiction weakens credibility.

Retail Practices: A direct sales promotion is presented, clearly aimed at increasing customer traffic. This confirms trading as a shop, not distributing aid under a foodbank model.

Stock Handling: The description of clutter and storage in vehicles points to improvised and unregulated shop management rather than structured charitable operations.

Financial Transparency: The speaker raises questions about other organisations charging for donated food, yet does not account for her own “bag for a fiver” sales. This selective criticism highlights inconsistencies in her own narrative.

Targeting Other Charities & Teachers: The transcript includes criticism of other local charities (labelled “abnormality”) and recounts conversations with a teacher about how donations and foodbank operations work. These comments appear designed to cast doubt on competitors, while positioning her own operation as more legitimate — despite the same unresolved contradictions.

– Sherlock

Did I actually hear her right when walking past two random people in the street. ‘That’s the one look, the son who sexually assaulted a worker’.

She needs to be very careful who and what she is videoing. Also my opinion is that she was walking in the opposite direction to avoid the Environmental Health Officer!

Automated Notice: Transcript Commentary

Speaker: “Jayne Price” (alias Carrie-Anne Ridsdale)

Business Representation: The transcript centres on sales of toys, branded shoes, ornaments, purses, and furniture. This is clearly retail trade, not foodbank distribution. It contradicts repeated public claims of being a “registered foodbank” or “not-for-profit charity shop.”

Volunteer Goods Taken Home: Donated stock is being removed by volunteers for private resale. No evidence of tracking or accountability is mentioned. For a legitimate charity, all stock should be processed through formal channels — this practice raises serious questions about where donations are really going.

Operational Capacity vs Claimed Disability: The speaker describes moving bags, heavy lifting, and handling large items. This is inconsistent with longstanding claims of being in “palliative care,” “housebound,” or severely disabled — narratives often used to justify benefits and Motability vehicle use.

Customer Behaviour and Attitude: Instead of addressing customer concerns, complaints are dismissed outright. This reflects a private business mindset rather than a public-facing charity or foodbank, where accountability and fair treatment would be expected.

Business Transparency: References to retail promotions (“fill a bag for £5”) confirm the shop is trading commercially. There is no mention of receipts, accounts, or regulatory oversight. Publicly, this continues to be framed as a charitable foodbank outlet, which risks misleading donors and customers.

Stock Handling and Safety: The transcript shows cluttered, ad-hoc stock management with goods stored in cars, back rooms, and tight spaces. This style of operation echoes prior Environmental Health concerns raised in official inspections.

– Sherlock